Back when my band and I were recording the Chip DiMonick "Not Yet Rated" album in 2007, the recording engineer/owner of the recording studio asked us, "Where are you guys getting this album mastered?" Huh? Our album needs to be mastered? What's that? And don't you do that here? Those are among the questions that flooded into our heads. (This was years before I did any music production/recording/mastering myself) It was a decision we weren't prepared for. So, we asked the engineer who he'd recommend. He recommended a guy in Chicago. Upon investigating the guy's website, it sounded like he specialized in mastering for vinyl records. And, in 2007, we had no interest in doing a vinyl pressing of our album. But, if our recording engineer had experience with him, we figured it would work out OK. We didn't really know what mastering did, so we didn't know who else might be better. Well, we started learning about mastering soon thereafter. After we sent in our unmastered recordings, we got back our mastered recordings. Something was very weird. On the songs we tuned down to C# on, we couldn't hear the low C#'s. "Is this even possible or are our ears playing tricks on us?" we wondered. I called the mastering engineer. He said that, because of the reference track we sent him - "Dead" by My Chemical Romance - he thought we'd want that C# eliminated so he cut that frequency. Still to this day, I have no idea why he would have thought this was a good idea. But he could restore it in a revision. And he did. The C# was back, but we still didn't exactly know how to evaluate how good the mastering was. Being 2007, this was during the peak of what was called "the loudness war," where mastering engineers competed almost exclusively on how loud they could make a recording. So, we put the master CD in back-to-back with our friends' CD. Theirs was louder. So, we asked the mastering engineer to make ours louder. He did. Without advising us what we'd be sacrificing in quality for loudness. But, not really knowing anything about mastering other than it can affect volume and take notes/frequencies right out of your songs, we were "satisfied." In hindsight, we could have done so better. The decision on who to master our album was ours. But, we were unprepared for it and were willing to blindly choose a mastering engineer just based on our recording engineer's recommendation (which could have been based on a kickback for all we knew). It's a regret. It's not 2007 anymore. The loudness war has been over for years. Streaming allows you to evaluate virtually unlimited examples of independently produced music. Yet, musicians STILL treat the mastering decision with the same ignorance and apathy as we did back then. In my post from a couple of weeks ago, I wrote that "because mastering is the last thing done to improve the sound of your music...it is a process that you should take seriously." I wish I someone gave me that advice 15 years ago. Careful consideration isn't just necessary when your recording engineer suggests a mastering studio. It's also necessary when your recording engineer suggests doing your mastering himself/herself, which is a topic all unto itself! I'll post on that in the near future. But, if you have the knowledge that mastering is a separate and necessary part of music production and the insight to know that you should choose the best mastering studio for your needs, we'd appreciate you considering Before and After Music Group's mastering services. Email us at beforeandaftermusicgroup@gmail.com or call/text us at 412-600-8241.

0 Comments

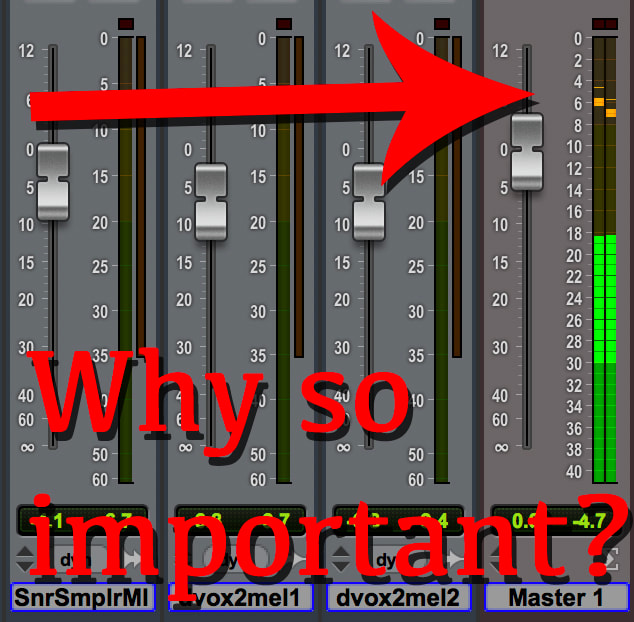

As I wrote in my post "9 Steps for Releasing Your Music," mastering is "the final – and critically important – process in getting your recorded music to sound as professional as possible." It is preceded by mixing, which is preceded by editing, which is preceded by overdubbing, which is preceded by tracking. So, it's natural to think that selecting a mastering studio doesn't need to be done until you are done mixing, or close to it. But, it's actually not smart to wait that long. And the reason isn't obvious unless you know a little technical tidbit about recording. Fortunately, that technical tidbit is relatively easy to understand, even if you're not an audio professional. So, here goes... Mastering studios will have preferred or required characteristics of mixes that help them make the greatest improvement in your music. One of those is "headroom." In digital recording, you have meters that show the volume of each vocal or instrument channel. You also have a single meter showing the volume of the mix - where all instruments are combined into a stereo channel representing left and right speakers. The channel for this meter is called the "master bus." These meters generally light up green (from the bottom to the middle of the meter and denoting acceptable volume), yellow (from the upper-middle to the near-top of the meter and denoting closeness to too loud), and red (the top of the meter and denoting definitively too loud). When a meter hits red in a digital recording, there is an unpleasant sound, kind of like a click, which is called "clipping." There are numbers alongside the meter which rise from negative numbers to 0. The point where clipping occurs is 0dBFS, which means 0 decibels full scale. You always want every channel and the master bus below 0dBFS. The distance between the loudest part of a signal during a song - the "peak" - and 0dBFS is called headroom. Most mastering studios will ask for a certain amount of headroom. For example, we - Before and After Music Group - ask for 3-6 dB of headroom. This means that the loudest part of your song should ideally not rise above -6dB on your studio's master bus and definitely not rise above -3dB on your studio's master bus. If you're curious why headroom is needed, it's to ensure that clipping is avoided in mastering, too. When a mastering engineer makes improvements to your recording - like boosting frequencies to give a recording more nationally-competitive bottom end or simply raising the overall volume of your recording after compressing it to an optimal dynamic range - that can push a recording closer to clipping. The more headroom we mastering engineers have to work with, the more improvements we can make without being slaves to the possibility of clipping. Still unsure what that has to do with selecting a mastering studio early? Well, when recording engineers begin a mix, they should have the target levels in mind. For example, I start mixing by dialing in the drums. If I know I have to leave 6dB of headroom, I will set levels for the drums so that - when soloed - they peak at around -11dB on the master bus. I know from experience that adding the other instruments in a standard rock song will add another 5-ish dB to the mix volume. So, when I have dialed everything else in, my mix should peak around -6dB. Some experienced recording and mixing engineers even "mix as they go." This means that, once the drums are tracked, they will set their faders to peak at a certain level so they are kind of "partially mixed" as other instruments are being recording on top of them. Therefore, it can be extremely helpful for your mixing engineer to know this before beginning a mix or, possibly, even beginning recording. If the mixing engineer doesn't know this up-front, s/he might complete an entire mix only to later learn that it doesn't jive well with the mastering studio's specs and that could result in more work to be done. For you, the musician, the client, that could mean more money spent unnecessarily. Don't let that happen. Decide on your mastering studio early. Get their specs. Share those specs with your mixing engineer before the mix begins. And let your mastering studio do the best job it can with improving the sound of your recording thanks to having a mix prepared ideally for them. Before and After Music Group would love to be selected as your mastering studio. If you want to ask us questions about mastering or get some guidance on how to navigate the music production process to get the best sounding final product for your music, contact us at beforeandaftermusicgroup@gmail.com or 412-600-8241. |

AuthorChip Dominick is the CEO and head mastering engineer for Before and After Music Group Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed